The combustion of fossil fuels has a significant impact on the environment. Products such as carbon monoxide (CO), carbon dioxide (CO2), oxides of nitrogen (NOx), oxides of sulfur (mostly SO2), and particulates are created in the combustion process and are discharged into the environment. While no entirely benign method of burning fossil fuels has been developed, numerous technological developments in combustion and combustion control permit these systems to be operated in a manner that significantly reduces their environmental impact.

In a Combustion Turbine (CT), there are several specific ways in which NOx reduction can be achieved:

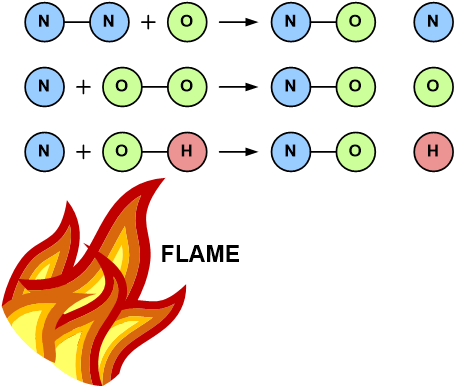

NOx is a gas that has chemical compounds made up of nitrogen and oxygen atoms. There are 12 different oxides of nitrogen, however, only two of these make up NOx which is a regulated atmospheric pollutant. NOx is the sum of nitric oxide (NO) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2), which are produced when burning fossil fuels, including the natural gas and #2 oil that is commonly burned in CTs; most of the NO generally oxidizes to form NO2. These two compounds together are called NOx.

The global emissions of NOx into the atmosphere have been increasing steadily since the middle of the last century. This is true because NOx is produced in the combustion of any fossil fuel, whether in cars, coal-fired boilers, or boilers burning biomass such as wood, trash, and other organic materials and fossil fuels. NOx contributes to acid rain, global warming, and adverse health effects (e.g. asthma) for human beings.

NOx is characterized by the source of nitrogen in the combustion process which contributes to the formation of NOx. The NOx, regardless of how it is created, is chemically identical. The first source of NOx is from the fuel itself. Some fossil fuels, especially coal, have nitrogen compounds in the fuel itself. When the source of nitrogen is the fuel (called fuel-bound nitrogen – FBN), it is sometimes referred to as “fuel NOx.” For fossil fuels, coal has the greatest amount of fuel-bound nitrogen, followed by #6 oil; #2 oil has very little FBN, and natural gas has essentially no fuel-bound nitrogen.

The second source of NOx is called thermal NOx. Thermal NOx is formed when the temperature of combustion is high enough to cause the nitrogen and oxygen in the combustion air to react to form NOx. The temperature of combustion must exceed 2,800°F to start producing thermal NOx; as the combustion temperature increases, the amount of thermal NOx is increased as well.

Given that most gas turbines burn natural gas and #2 oil, fuel NOx is essentially zero. Thermal NOx is a problem for both fuel oil and natural gas, but the NOx emissions are generally higher when firing oil than natural gas because the combustion temperature is higher with oil than gas.

In conventional combustion systems, the combustion air is admitted into the area of combustion, where it mixes with the fuel in a process called diffusion. Operation at high combustion temperatures increases CT efficiency but also increases thermal NOx production. Further, burning fuel (both gas and liquid) with diffusion mixing results in “hot spots.”

There are several design strategies to limit the formation of thermal NOx in gas turbines, but all of these strategies involve lowering the temperature of combustion. The earliest way that combustion temperatures were reduced when burning either gas or oil was through injection of either steam or, more commonly, water.

There are issues with steam and water injection. First, the CT combustion temperature, and thus the load, must be high enough (typically around 20% of rated gross output) to prevent the injected water or steam from extinguishing the flame. Second, steam and water injection reduces the CT efficiency. Third, if there is too much steam, or more commonly water injection, even at full load, there is incomplete combustion, which causes incomplete combustion and so increases carbon monoxide (CO) emissions; CO is also an air pollutant. These issues mean that there are limits to how low the NOx emissions can be using steam/water injection.

The use of water/steam injection can bring NOx emissions from more than 100 ppmvd (parts per million by volume, dry) to about 25 ppmvd when firing gas and 42 ppmvd when firing liquid fuel. The abbreviation “ppmvd” in the table stands for “parts per million, dry.” This means that the NOx concentrations assume that the water in the exhaust gas is condensed, and therefore is “dry.”

The most common way to reduce flame temperatures in “modern” industrial CTs (those sold from about 1990 on) when burning gas is through the use of lean premix, also called dry low NOx (DLN), combustion systems.

The word lean in lean premix means that the fuel is burned with just enough combustion air to prevent the flame from being unstable; flame instability often results in flameout and/or damage to the combustion system. Since reducing combustion air tends to decrease combustion temperature, thermal NOx production is reduced.

The term premix refers to the fact that in these combustion systems, the gas and combustion air are mixed before the fuel is ignited in the combustion system burners. By premixing the air and gas fuel before combustion systems, hot spots that increase NOx production are nearly eliminated, further reducing thermal NOx production. It is possible to achieve NOx emissions of 5 ppmvd, and sometimes lower, firing gas with lean-premix systems.

In lean-premix DLN systems, the combustion system must be started in the diffusion mode because the combustion temperature is too low to maintain stable combustion with the lean airflow used in normal operation. Diffusion combustion is used until the load is, and thus the combustion chamber temperature is high enough to sustain stable operation with the low airflow that is required to operate in the lean-premix/DLN mode of operation. The minimal load for lean premix/DLN operation is typically about 40% to 50% of the full load). When the load falls, the combustion system mode of operation changes from lean-premix/DLN to diffusion combustion. Operation below the load required for lean-premix operation results in higher CT NOx emissions.

Most CTs with lean-premix/DLN combustion systems use Variable Inlet Guide Vanes (VIGVs) to control airflow to the combustion system. At low loads, the IGVs are positioned to reduce airflow since the amount of fuel burned is low; controlling airflow to the combustion system can reduce excessive combustion temperature, thus reducing thermal NOx production at low loads. As CT load (and fuel flow) increases, the VIGVs are opened to increase airflow in coordination with fuel valves that control fuel flow to the combustion system. In combined cycle plants (described below) VIGVs are also modulated to control CT exhaust temperature entering the HRSG; combined cycle plants and HRSGs are described later.

The lean-premix combustion scheme cannot be used when burning liquid fuel. Accordingly, even lean premix/DLN combustion systems use water injection when firing liquid fuels.

As with conventional combustion systems, the use of water injection to limit NOx production is not possible to inject water until the load, and thus combustion temperature is high enough to prevent flame instability and possible loss of flame when water is injected. The minimum load that produces a combustion temperature high enough for operation with water injection varies among gas turbine manufacturers and models. Operation at loads lower than that required for water injection results in higher CT NOx emissions.

To optimize the operation of lean-premix DLN combustion systems, close coordination of the operation of VIGVs and the different fuel valves that control gas flow in both the diffusion and lean-premix. Trained technicians (often from the CT manufacturer) make adjustments to the sequencing of fuel valves and the positioning of VIGVs to maintain low NOx emissions. The process of making these adjustments is called tuning the combustion system.

It is important to know that there are many older CTs that do not have lean-premix DLN combustion systems. Most of these older gas turbines use water injection to limit NOx production whether burning oil or gas.

One of the ways to increase gas turbine efficiency is to increase a parameter called the firing temperature; firing temperature is the temperature of the exhaust gas at the first stage of the turbine section of the CT. The newest CTs have high firing temperatures to obtain competitive efficiencies. This means that these new CTs produce more NOx (typically around 25 ppmvd) than some older (vintage 1990s) gas turbines, even when firing gas in lean-premix combustion systems. To meet regulatory limits of NOx in many locations, it is necessary to use so-called post-combustion NOx controls. For CTs, the post-combustion control used is the SCR.

The use of low NOx combustion systems reduces NOx emissions considerably, however, regulatory limits in many locations have NOx emission limits (commonly 2-3 ppmvd), which are lower than can be achieved using low NOx combustion systems. To meet these NOx limits, CTs are equipped with a Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR) system.

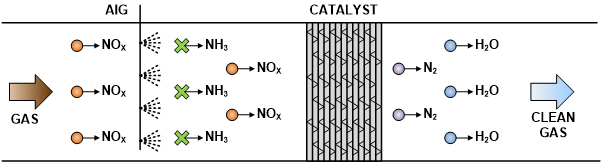

In the SCR system ammonia (NH3) or urea (CO(NH2)2) is injected into exhaust gas ductwork upstream of a grid with a catalyst coating. A catalyst is a substance that must be present for a chemical reaction to take place that is not consumed in the reaction. The most common SCR catalysts are oxides of titanium, tungsten and vanadium, or zeolites. In the presence of the catalyst, the ammonia reacts with the NOx in the exhaust gas; the products of the reaction are diatomic nitrogen (N2) and water (H2O).

The temperature of the exhaust gas has a significant influence on the efficiency of the reaction, with the optimum temperature being about 675°F to 840°F. At both lower and higher temperatures, the reaction is less efficient, resulting in uncatalyzed NOx, which increases NOx emissions, and increased ammonia slip. Ammonia slip is ammonia that does not react with the NOx, and so is in the exhaust gas at the stack. At excessive temperatures, the catalyst can be damaged as well.

During startup and shutdown of gas turbines, the exhaust temperatures are lower than normal and so NOx emissions are higher than normal during startup and shutdown. The range of temperature required for SCR operation presents a problem for the application of SCRs for most gas turbines because the temperature at the gas turbine exhaust may be above or near the upper end of the acceptable temperature range.

There are two ways in which SCRs can be used to limit CT NOx emissions.

Regardless of whether a CT is operating in a combined cycle plant or a simple cycle, the use of SCRs can reduce NOx to the limits required by regulation. SCRs that are installed in both combined cycle plants and simple cycle CTs cannot be placed in operation until the CT load is high enough for the exhaust gas temperature to be high enough for SCR operation. Accordingly, operation at loads below that required for SCR operation results in higher NOx emissions.

The operating permits for plants with CTs and SCRs commonly allow higher than normal NOx emissions briefly in startup and shutdown when low load operation is necessary. SCR catalysts can become fouled, most often when oil is fired; when the SCR catalyst is fouled, NOx emissions increase. The fouling can be removed by cleaning. SCR catalysts have a limited life and are then replaced. When CT SCR catalyst can have a lifetime of around 25,000 hours, however, the actual lifetime varies and both NOx emissions and ammonia/urea consumption must be monitored to determine when the catalyst requires replacement.